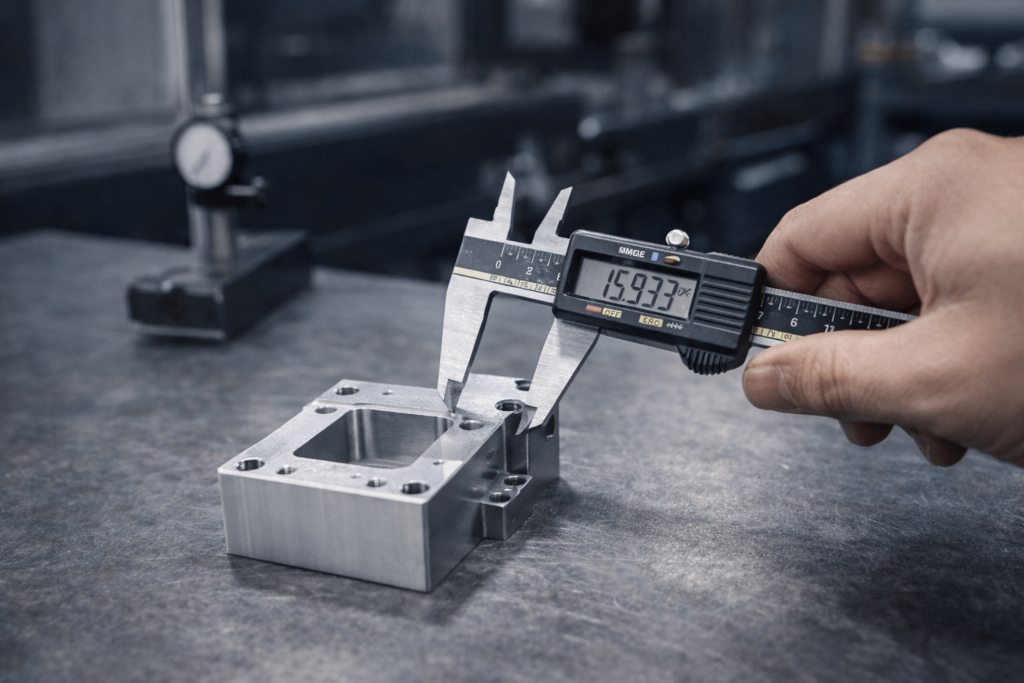

Lathe machining parts look simple on paper: a few diameters, a length, a thread, maybe a groove. In global sourcing, that simplicity often creates a blind spot. The first sample may measure perfectly, yet the next few thousand pieces can drift just enough to slow assembly, trigger sorting, or introduce delivery risk.

For overseas wholesale procurement teams, the real objective is not “one good part.” It is stable supply: predictable variation, repeatable output, and controlled risk across batches, shifts, and tool life. This article is written for buyers and engineers who source CNC turning at volume and need a practical way to evaluate suppliers without turning every RFQ into a prolonged engineering audit.

Rather than explaining how a lathe works, the focus here is on how lathe machining parts behave in real production systems, why early approvals often mislead, and how procurement teams can ask the right questions to achieve high conversion with low long‑term risk.

Why “Simple” Lathe Machining Parts Are Commonly Misjudged

In procurement workflows, “simple” often implies fast quoting, easy inspection, and low switching cost. Many lathe machining parts fit that mental model, so sourcing decisions naturally emphasize unit price and lead time. This approach works when downstream processes are tolerant to variation.

However, many turned components sit at functional interfaces: press fits, sliding contacts, sealing surfaces, threaded joints, bearing seats, and concentric assemblies. In these applications, “within tolerance” does not always mean “consistent in assembly.” A part can pass gauges and still cause intermittent issues because the process is drifting in ways routine sampling does not capture.

Early prototypes reinforce this misjudgment. First articles are produced under favorable conditions—new tools, close operator attention, short run time, and limited exposure to material‑lot variation. What is validated is feasibility, not stability. For wholesale buyers, the practical framing is simple: lathe machining parts are only low‑risk when the process is repeatable, not when the drawing looks simple.

Lathe Machining Behaves as a Continuous System, Not Independent Cycles

CNC turning is often described as a sequence of repeatable cycles: load, cut, unload, measure. In production, it behaves as a continuous system with memory. The workpiece rotates without interruption, the cutting edge engages continuously, and heat, force, and wear accumulate over time.

Three variables change even when the program does not: tool condition, temperature, and material response. Tool wear gradually alters edge geometry. Machine and part temperature rise toward steady state, affecting expansion and alignment. Residual stress relaxes and interacts with clamping distortion. Each change is small, but together they shift how the process behaves.

For procurement teams, this explains a common frustration: a supplier delivers a perfect first article, yet later batches feel different in assembly while still measuring “OK.” Accuracy is a snapshot. Repeatability is a time‑based capability. Evaluating turning suppliers based only on early measurements approves a process before it has revealed how it behaves under real production time.

Process Drift Begins Before Dimensions Go Out of Tolerance

Many sourcing problems start with a timing error. Teams assume a process is stable until measurements fail. In reality, drift usually begins earlier, and the earliest signals are often qualitative rather than numeric.

Surface condition is a common first indicator. Tool marks may change subtly, or surface texture may feel different during handling. Average roughness values can remain within specification while functional behavior changes, especially for sliding or sealing surfaces. Standards such as ISO 1302 and ISO 4287/4288 define what is measured, but they do not fully predict how a surface will behave under load or lubrication.

Assembly feedback provides another early signal. Press‑fit force may trend upward over a run. Thread torque may feel inconsistent even when gauges pass. A sealing face may appear acceptable but leak intermittently because micro‑interaction has shifted. For procurement teams, these signals matter because they precede sorting, rework, and line interruptions.

Early signals buyers can watch during pilot and early production

| Early signal in turned parts | Likely underlying change | Procurement impact |

|---|---|---|

| Tool marks shift or sharpen | Tool wear, vibration change | Predicts later drift and higher rework |

| Press‑fit force trends | Thermal state or clamping distortion | Causes line delays |

| Thread torque inconsistent | Insert wear or chip control issues | Leads to intermittent failures |

| “OK” dimensions, poor fit | Surface/geometry interaction drift | Triggers sorting and disputes |

A supplier who can explain how these signals are monitored and controlled presents lower sourcing risk than one who relies solely on periodic inspection reports.

Lathe Components as Stability Amplifiers: A Procurement View

Search results for “lathe components” often list parts such as the headstock, bed, chuck, tailstock, turret, and toolholder. For procurement, the more useful question is not what these components are, but how they influence consistency.

The chuck is a common amplifier. Clamping force and jaw contact can distort thin‑walled or softer parts before cutting begins. Parts may measure round while clamped and relax after release, creating differences between inspection and assembly conditions.

The lathe bed and spindle amplify thermal behavior. Small temperature changes can shift alignment enough to matter when tolerances are tight. As a reference, steel expands roughly 11–13 µm per meter per °C, while aluminum expands around 23 µm per meter per °C. Over typical turned‑part lengths, this becomes relevant when fits are sensitive.

The turret and toolholder amplify rigidity effects. Minor changes in stiffness can translate into visible surface waviness or roundness variation. Tailstocks stabilize long parts but can introduce axial stress if misaligned or over‑pressurized.

From a buyer’s perspective, asking “what lathe do you use” offers limited insight. More revealing questions focus on control practices: clamping strategy, warm‑up routine, insert change discipline, offset policy, and in‑process trend monitoring. These determine whether lathe machining parts remain stable across batches.

Why the Same Drawing Rarely Produces Identical Lathe Machining Parts

A drawing defines geometry, tolerances, and material grade. It does not define the manufacturing state that produces the part. This gap explains why two suppliers can meet the same drawing requirements yet deliver different stability outcomes.

Material behavior is one driver. Even within the same grade, bar stock can vary in straightness, residual stress, and hardness distribution. These differences affect chip formation, tool wear rate, and springback after cutting.

Workholding is another driver. Overhang length, jaw geometry, and clamping pressure change how a part deflects during machining and how it relaxes afterward. Time is the third missing dimension. Tool wear, coolant condition, and machine thermal equilibrium evolve during production but are invisible on the drawing.

For procurement teams, the implication is clear: meeting the print is necessary, not sufficient. Reliable supply of lathe machining parts requires alignment between drawing intent and process behavior.

Prototype Success Does Not Guarantee Batch Stability

Prototype success confirms feasibility, not long‑run stability. Sampling conditions are unusually favorable: new tools, frequent adjustments, short run times, and limited material‑lot exposure.

In volume production, economics change the system. Tool wear becomes routine. Material‑lot variation becomes unavoidable. Longer runs create new thermal states. Small setup differences across shifts begin to matter.

A procurement‑friendly way to validate prototypes is to treat them as a process interview. Ask what changes between prototype and production: tool‑change triggers, offset control approach, warm‑up practices, and material‑lot validation. Clear answers indicate lower risk than perfect sample photos.

Accuracy Alone Does Not Define Supply Reliability

Accuracy is easy to specify and verify. Repeatability is harder to demonstrate, yet it determines whether supply remains stable at scale.

A turning process can hit tight tolerances intermittently while remaining unstable. Variation may move within the tolerance band, or surface interaction may change even though dimensions do not. Over‑specifying tolerances can increase sensitivity without improving function.

Standards help structure intent. ISO 1101 clarifies form and position. ISO 286 defines fits. ISO 2768 provides general tolerances where appropriate. These do not guarantee stability, but they reduce ambiguity and support better supplier conversations focused on repeatability rather than snapshots.

Inspection Confirms Results but Does Not Control the Process

Inspection records what has already happened. It does not prevent drift.

Increasing inspection frequency can reduce escapes, but it also raises cost and lead time. Sorting and rework become more common while the underlying process may remain unstable.

Suppliers who manage tool life, standardize setups, and monitor trends can explain why variation occurs and how it is controlled. For procurement teams, this explanatory capability is a stronger reliability signal than inspection volume alone.

The Hidden Cost of Inconsistent Lathe Machining Parts

Many machining problems do not appear as scrap. They surface as assembly inefficiency: inconsistent fit, extra force, intermittent torque, or unexpected sorting.

These costs accumulate across departments. Operators compensate. Quality teams add containment. Procurement manages pressure from delivery delays. Unit price savings can quickly disappear.

For wholesale buyers focused on total cost of ownership, stability matters more than headline price. Suppliers who design turning processes for repeatability often reduce indirect cost even if their quoted price is not the lowest.

A Procurement‑Oriented Framework for Evaluating Lathe Machining Parts

A reliable sourcing approach evaluates the turning system over time, not just samples. This does not require complex audits—only focused questions.

First, define what stability means for your application. Is the risk dimensional drift, inconsistent fit, surface interaction, or concentricity behavior? Second, ask control‑oriented questions: how insert life is managed, how setups are standardized, how new material lots are validated, and how trends are detected before failure.

Third, align drawing strategy with function. Use GD&T and fits where necessary, avoid unnecessary tightening, and confirm inspection conditions match assembly conditions. This reduces the risk of “passing parts that behave differently.”

Manufacturers such as YISHANG support this evaluation style because it reflects real production behavior. The goal is not to impress with one perfect sample, but to deliver predictable, repeatable output across volume.

Closing Perspective for Wholesale Buyers

Lathe machining parts rarely fail loudly. More often, they drift quietly until costs surface downstream. Approving suppliers too early—before repeatability is demonstrated—is a common sourcing mistake.

If you are sourcing CNC turning at volume and want to reduce batch variation and delivery risk, a short system‑level discussion can prevent months of downstream issues. YISHANG can review your RFQ priorities and stability requirements and help identify risk early.

If useful, share basic part details and annual volume. We’ll respond with practical questions and recommendations focused on repeatable supply rather than one‑time samples.