When overseas buyers search for a metal supplier, they are rarely trying to learn machining for themselves. They want to know whether the factory behind the website can handle real production: stable quality, consistent tolerances, and reliable lead times.

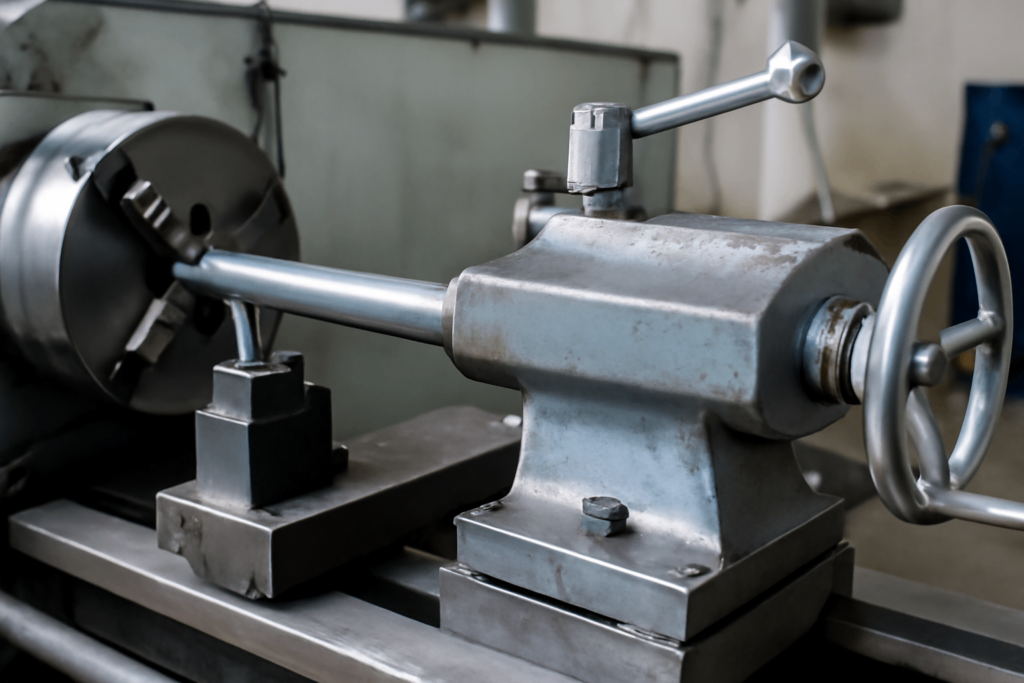

Understanding how to work a lathe machine in a production environment is a core part of that story. A metal lathe is not just a piece of equipment; it is a process that directly affects fit, function, and lifecycle of the final product.

In this article, we look at lathe machining from a manufacturing and procurement perspective. We focus on what matters to buyers handling volume orders, OEM projects, and long-term programs, and how a professional supplier such as

YISHANG approaches lathe work to support those expectations.

Quick Overview: How to Operate a Metal Lathe in a Production Shop

Before diving into details, it helps to align expectations between technical and purchasing teams. When a professional shop explains how to operate a metal lathe, the answer is rarely a simple list of buttons and levers. Instead, it is a workflow built around four linked ideas: preparation, workholding, controlled cutting, and in-process verification.

First, the machine and work area are prepared. The lathe is cleaned, jaws are checked, the correct chuck or fixture is installed, and the workpiece is inspected. This step is where a lot of risk can be removed. A good setup ensures that the part will not move, twist, or flex unexpectedly once cutting starts.

Second, the part is clamped and centered. On a simple bar this may be straightforward, but many industrial parts are welded, bent, or irregular. In those cases, the operator chooses where to reference the part, how hard to clamp, and what support to add. This is where experience separates an ordinary lathe user from a production-focused machinist.

Third, cutting begins with conservative, well-judged parameters. In a training video about how to operate a metal lathe, this might look like a clean, single pass. In real production, it is more dynamic. Operators watch chip shape, listen for vibration, and feel the load on the machine. They may adjust speed or feed slightly to keep the process within a stable window.

Finally, measurements and surface checks are made during the run, not only afterward. Diameters, lengths, and critical features are verified with gauges and micrometers. When something starts to drift, offsets and methods are corrected. This combination of preparation, controlled cutting, and feedback is what makes manual lathe operation or CNC turning suitable for volume orders.

For wholesale buyers, understanding this high-level workflow is often more useful than knowing every internal part of the machine. It shows that the supplier treats turning as a controlled process, not a sequence of improvisations.

What Wholesale Buyers Really Need from Lathe Machining

Reliability and Repeatability for Volume Orders

For a wholesale buyer, a “good” supplier is not the one who can make a perfect sample once. It is the one who can keep that level of quality across hundreds or thousands of pieces, month after month.

In lathe work, that repeatability starts with stability. When a factory runs mild steel, stainless steel, or aluminum on a manual lathe or CNC lathe, the machine must absorb cutting forces without excessive vibration or drift.

A slightly unstable setup might still produce an acceptable first part. But over a long production run, that instability shows up as size variation, poor surface finish, and growing deviation from the drawing.

From a buyer’s point of view, this creates risk. Inconsistent parts cause delays in assembly, increase inspection time, and may even lead to entire batches being rejected at the warehouse or at the end customer’s site.

A supplier who understands stability as more than just “the machine does not shake” is much more valuable. They consider the full system: machine rigidity, tool overhang, workpiece length, chuck condition, and material hardness.

This mindset is what separates a basic lathe user from a production-level machining partner.

How Machining Choices Affect Lead Time and Cost

Every decision made at the lathe affects cost and schedule. Cutting parameters influence cycle time, but they also influence scrap rate, tool life, and rework needs.

If a supplier runs a lathe too aggressively on stainless steel, tools fail early and parts may go out of tolerance near the end of the shift. If they run too gently, the cycle time becomes uncompetitive and capacity suffers.

For buyers, the question behind “how to operate a metal lathe” is really: can this supplier control the process well enough to give me predictable lead times and stable unit prices?

A factory that manages speed, feed, tool selection, and inspection in a structured way does more than make parts. It supports business planning, inventory control, and customer satisfaction across the buyer’s own network.

Before the First Cut: Stability, Safety, Material Behavior and Preparation

Stability and Rigidity in Industrial Conditions

In a training setting, “how to work a lathe machine” often starts with identifying parts of the machine. In a production shop, it starts with one question: is the setup rigid enough for the job?

When turning a short mild steel shaft, a three-jaw chuck with proper clamping pressure may be enough. When turning a long tube, a steady rest or tailstock support becomes essential to prevent bending and oscillation.

For stainless steel, cutting forces are higher. A small amount of tool overhang that is acceptable on aluminum might cause deflection and vibration on harder materials.

An industrial metal lathe operator learns to read these conditions quickly. They listen to how the machine behaves under load, and they know when a setup is close to its limits.

Wholesale buyers can infer a supplier’s level of maturity by how clearly they explain these considerations. A factory that talks about stability only in general terms may still be learning. A factory that explains how rigidity, clamping, and material hardness interact is usually more ready for volume business.

Safety and Risk Awareness in Metal Turning

Any discussion about how to operate a metal lathe in the real world must include safety. For buyers, this is not only a human concern but a business concern. Shops with weak safety culture are more likely to suffer downtime, staff turnover, and quality escapes.

Core practices are simple but powerful. Operators wear appropriate eye and hand protection. Loose clothing, jewelry, and long hair are controlled before anyone approaches a rotating spindle. Emergency stops are tested, and guards are kept in place instead of being bypassed for convenience.

From a production perspective, safe habits and stable processes go together. A machinist who respects safety procedures usually respects setup and inspection procedures as well. When a supplier shows that it treats lathe safety and process control as part of the same discipline, it sends a strong signal about long-term reliability.

Material Behavior and Its Impact on Turning Strategy

Not all metals behave the same way on a lathe. For buyers, this detail matters because it influences pricing, lead time, and quality risk.

Mild steel offers balanced machinability. It produces predictable chips and allows a wide window of speeds and feeds, which is ideal for stable batch production.

Stainless steel work-hardens as it is cut. If feed is too low or the tool is dull, the surface hardens, cutting becomes more difficult, and tool life drops sharply.

Aluminum is soft and allows high cutting speeds, but it tends to form long, continuous chips. If chip control is poor or the cutting edge is not sharp, chips can wrap around the part or tool, damaging the surface or even stopping the machine.

A supplier who understands these behaviors does not treat “steel” as a single category. Instead, they tune their manual lathe operation or CNC programs to each material, balancing efficiency with tolerance needs.

From a procurement angle, this means fewer surprises. Projects move with more predictable timing, and the cost of quality—inspection, sorting, rework—stays under control.

Preparation as the Foundation for Dimensional Stability

Most machining problems start before the tool touches the workpiece. Preparation is where many suppliers either show discipline or reveal risk.

On a practical level, preparation includes checking runout, cleaning the chuck jaws, verifying that the workpiece seats flat, and confirming that no burrs or distortions interfere with clamping.

When dealing with welded components, residual stress may cause a tube or frame to move slightly when clamped. A skilled operator anticipates this and chooses a clamping strategy that minimizes deformation.

For extruded or bent parts, small shape variations are common. The supplier must decide where to reference the part so that critical dimensions remain correct after machining.

This attention to preparation is not a theoretical point. It is a direct indicator of whether the factory can keep tolerances stable across an entire batch.

For buyers, asking how a supplier sets up critical parts on the lathe is often more revealing than asking what machines they own.

Working a Lathe Machine in a Real Production Environment

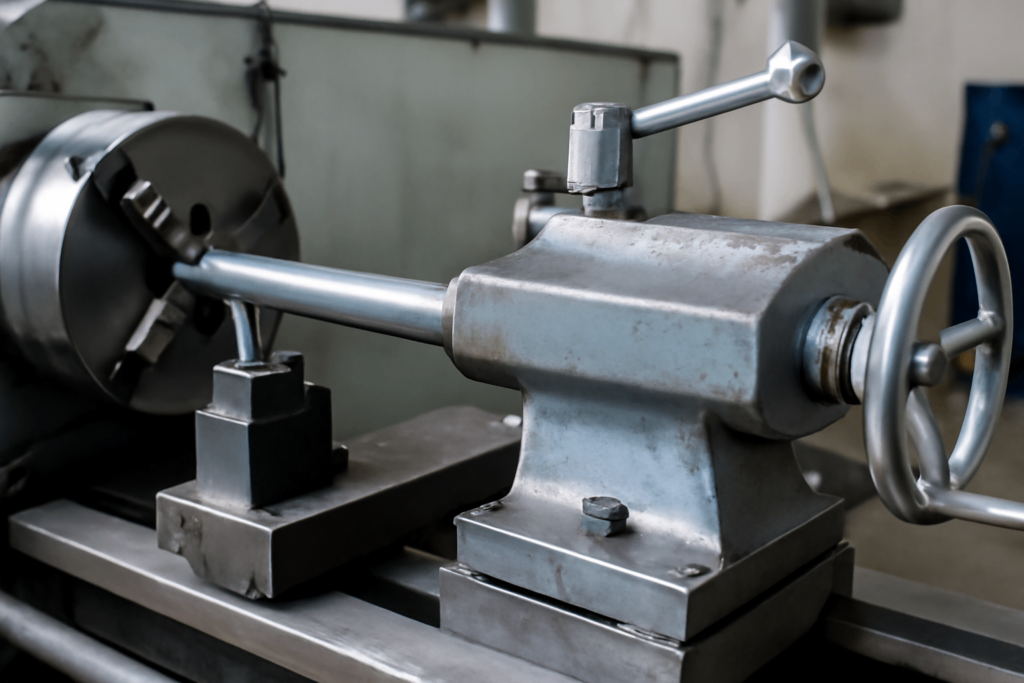

Workholding and Centering Strategy

Once preparation is complete, the next priority is workholding. In production, the question is not simply “is the part clamped,” but “is it clamped repeatably and without deformation?”

A round bar held in a three-jaw chuck may be straightforward. But many industrial parts are not simple cylinders. Brackets, housings, welded flanges, or irregular shafts often require four-jaw chucks, custom soft jaws, or dedicated fixtures.

When a part is clamped in a non-ideal way, the centerline might shift under cutting force. This leads to eccentricity, taper, or uneven wear, especially during long runs.

A supplier who knows how to operate a metal lathe at production level will choose the right chuck and support method, balance clamping pressure to avoid distortion, and verify concentricity using indicators or trial cuts.

For a buyer, this translates into fewer surprises at assembly. Parts fit better, alignment issues decrease, and internal quality teams spend less time sorting borderline components.

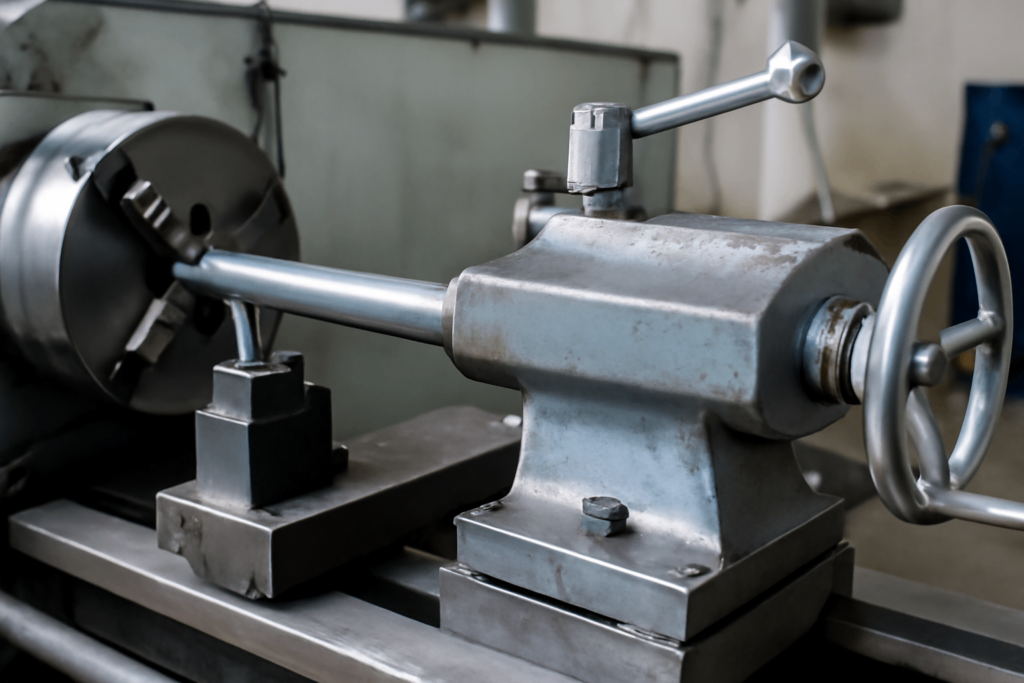

Tool Setup: Height, Projection and Edge Condition

Tooling is another area where production stability is either protected or destroyed. Tool height must match the centerline closely. Too high and the tool rubs instead of cutting; too low and it digs in and increases load on the machine.

Projection—the length of the tool sticking out of the holder—should be as short as practical. Long projection amplifies deflection, especially on hard materials and deep cuts.

Edge condition is equally important. A slightly chipped insert or dull high-speed steel tool might still cut, but it produces more heat, more variation, and a rougher surface.

In a one-off situation, a machinist might compensate manually. In a batch environment, such inconsistencies accumulate.

Professional shops set standards for tool setup and inspection. They define when to index inserts, when to replace tools, and how to document tool changes for traceability.

For procurement teams, this level of control signals that the supplier is ready to support larger, more demanding programs.

Parameter Choices and the Role of the First Pass

Speed, feed, and depth of cut determine how smooth and efficient the turning operation will be. They also influence tool life and part integrity.

Rather than rely only on tables, experienced operators watch the process. They observe chip shape, listen to the cutting sound, and feel whether the machine is working within a stable range.

The first pass is often used as a diagnostic cut. It is kept shallow, not to save time, but to gather information: Is there chatter starting? Does the part deflect? Is the surface responding as expected?

Based on that feedback, operators refine parameters before committing to deeper cuts or multiple passes.

This approach is what makes the difference between a shop that reacts to problems after they happen and a shop that prevents problems from affecting entire batches.

In-Process Quality Control and Defect Prevention

Reading Sound, Chip Pattern, Temperature and Finish

Quality control is not only a final inspection step. During turning, operators receive continuous feedback from the process itself.

Sound is one of the fastest indicators. A steady tone suggests stable cutting. A pulsing or high-pitched vibration sound warns of chatter or tool resonance.

Chip pattern tells another part of the story. Short, curled chips often indicate a good balance between feed and speed. Long, stringy chips can mean the feed is too low or the rake angle is not ideal.

Temperature, felt at the tool, workpiece, and chips, shows whether heat is being managed correctly. Too much heat can cause micro-cracks, hardness changes, or distortion in thin-walled parts.

Surface finish is the visible summary. A uniform finish with consistent tool marks reflects stable conditions. Random patterns, vibration marks, or rough patches point to underlying issues.

A supplier who trains operators to read and respond to these signs gives buyers more confidence that problems will be caught early, not at the loading dock.

Preventing Chatter, Deflection and Surface Problems

Chatter, deflection, and poor finish are not just technical issues; they are cost drivers. They can reduce tool life, increase scrap, and create extra inspection work.

Chatter happens when the tool vibrates instead of cutting smoothly. This can be addressed by changing spindle speed, adjusting depth of cut, improving rigidity, or changing tool geometry.

Deflection occurs when the workpiece or tool bends under load. It shows up as taper, out-of-round conditions, or inconsistent diameters along the length.

Surface problems may come from a dull tool, an unstable setup, or incorrect feed. They often lead to aesthetic concerns, coating issues, or fit problems.

A supplier that knows how to operate a metal lathe with a focus on prevention does not simply accept these defects as “normal.” They have methods to reduce risk before it translates into shipment delays or field complaints.

For buyers, understanding how a factory approaches these issues is as important as knowing what machines they own.

In-Process Measurement and On-the-Fly Adjustments

Even the best setups experience variation over time. Tools wear, materials change slightly, and temperature affects dimensions.

In-process measurement bridges the gap between theory and reality. Operators use micrometers, bore gauges, and indicators to check critical features during the run, not only at the end.

If a diameter begins to drift toward the tolerance limit, offsets can be adjusted. If a feature shows a consistent deviation, the program or manual approach can be fine-tuned.

This real-time control is crucial for long runs, for parts used in assemblies, and for components affecting safety or performance.

Wholesale buyers benefit directly from this discipline: fewer surprises, fewer emergency re-sorts, and a smoother flow of goods through their own warehouses.

Lathe Machining Inside a Complete Fabrication Flow

Single-Part versus Batch Thinking

There is a big difference between machining a prototype and machining a production batch. In a prototype, the machinist can make manual adjustments, take extra measurements, and accept longer cycle times.

In a batch, the process has to be robust. Setups must be repeatable, tools must be predictable, and inspections must be efficient.

A factory that thinks in batch terms when planning lathe work will design setups that can be reproduced, standardize tool choices, and structure inspection so it scales with volume.

For buyers, this is exactly the kind of thinking that supports long-term contracts and ongoing replenishment programs.

Machining Welded, Formed and Complex Structures

Many industrial products are not simple turned bars. They include welded flanges, bent tubes, brackets with pre-formed shapes, or assemblies that must be finished on a lathe.

These parts come with additional challenges. Welded joints may have different hardness compared to base material. Bending can introduce internal stress that changes when the part is clamped.

A supplier with real experience in how to work a lathe machine on such structures will choose clamping points carefully, support long arms or thin walls, and adjust parameters near heat-affected zones.

This capability reduces the buyer’s need for multiple suppliers. More operations can be completed under one roof, simplifying logistics and quality management.

Integration with Cutting, Bending, Welding and Finishing

Lathe machining rarely stands alone in a metal product’s lifecycle. Parts are cut, bent, welded, machined, and finished in sequence.

When cutting produces a rough edge or an inaccurate blank, the lathe operation becomes responsible for restoring accuracy. Should bending create any twist, the centering process on the lathe immediately grows more demanding. And when welding causes distortion, machining must step in—either to correct the deviation or adapt the process to maintain dimensional integrity.

A supplier that looks at turning as one step in the full flow can coordinate tolerances, choose reference points, and schedule processes in an intelligent sequence.

For wholesale buyers and importers, this integration simplifies communication. Instead of managing several separate operations across different factories, they can rely on a partner who understands how each operation affects the next.

Lessons from the Shop Floor: What They Mean for Buyers

High-Impact Operator Errors and How Mature Shops Avoid Them

Every shop faces operator mistakes, but mature shops design systems to reduce their impact.

Common high-impact errors include clamping a part in a way that looks secure but allows gradual movement, misreading chatter and changing the wrong parameter, and ignoring small tool defects until they cause scrap.

A supplier prepared for global wholesale work trains operators to spot these issues early. They combine on-the-job mentoring with clear standards for tool change, setup checks, and measurement.

For buyers, this is not just a technical detail. It is evidence that the supplier understands that every mistake costs time, money, and sometimes reputation in the end market.

Training, Documentation and Process Discipline

Skill on the lathe is built over time, but it grows faster with structure. Focused practice on facing, consistent turning, and specific tolerance work builds intuition.

However, intuition alone is not enough in a production environment. Factories that serve volume customers document settings, tool lives, and inspection frequencies. They maintain machining logs, link them with drawing revisions, and review performance to improve future runs.

This kind of discipline is invisible in photos of machines, but highly visible in stability of supply. It is a major reason why some suppliers become long-term partners while others remain risky options.

Conclusion

For global wholesale buyers, the question behind

how to work a lathe machine is not “how do I learn this myself,” but “how does my supplier manage this process on my behalf?”

A professional approach to lathe work—stable setups, material-aware strategies, thoughtful parameter choices, real-time quality control, and integrated process planning—translates directly into better project outcomes.

It means fewer delays, fewer surprises, and fewer quality disputes. It means metal parts that arrive ready for assembly, not ready for rework.

If you are looking for a machining partner who understands these realities and applies them in daily production,

YISHANG is ready to discuss your next metal fabrication project.