Before diving into details, here is the short, search-intent friendly answer many buyers look for:

- Highest melting point metal:

Tungsten (W) — about 3422 °C (6192 °F) among all pure metals. - Highest melting point alloy (commonly cited):

Tungsten–hafnium carbide (WHC) — a refractory alloy system with one of the highest melting points reported for engineered alloys, used in extreme aerospace and industrial applications. - Highest melting point material (compound):

Carbides such as tantalum hafnium carbide, Ta₄HfC₅, are often referenced in research as candidates for the highest melting temperature material known, with melting temperatures estimated above 4000 °C.

However, for overseas industrial buyers sourcing metal products, the more important question is not just what substance has the highest melting point, but:

Which commercially available alloy will perform reliably and cost-effectively in my actual temperature range and application?

The rest of this guide answers that question from a procurement and fabrication perspective.

Why Melting Points Matter to Overseas Procurement Teams

For overseas procurement teams, melting point is not just a number on a material data sheet.

It is a risk indicator that affects material selection, fabrication feasibility, structural reliability, and lifetime cost.

When you place a large order for sheet-metal housings, welded frames, machine guards, battery cases, or CNC-machined brackets, you are responsible for more than unit price.

You also need to know whether those metal parts will stay dimensionally stable when exposed to welding heat, operating temperature, or thermal cycling in the field.

Many buyers search for what has the highest melting point or highest melting point material hoping to find a “bulletproof” solution.

In practice, the smarter question is: Which metal or alloy offers the right balance of melting behavior, strength at temperature, process compatibility, and cost for my specific application?

This guide is written from a manufacturing perspective.

It explains what melting point really means in production, how it interacts with welding and coatings, what materials actually achieve the highest melting temperature, and how a supplier like YISHANG uses this understanding when producing industrial metal parts for global customers.

What Melting Point Means in Real Manufacturing Scenarios

In textbooks, the melting point is the temperature at which a solid becomes a liquid.

In industrial manufacturing, what matters more is: At what temperature does this material stop doing its job?

A bracket does not need to melt to fail.

A housing does not need to liquefy to leak.

Most components fail much earlier through softening, distortion, or coating breakdown.

Melting, Softening, Sublimation, and Thermal Failure

From a buyer’s standpoint, several temperature thresholds are more relevant than a single melting-point value:

- Softening temperature – the point where a metal begins to lose stiffness and load-bearing capacity.

This is critical for frames, enclosures, racks, and structural weldments. - Thermal deformation – the temperature at which shape and dimensions change enough to affect fit, sealing, or alignment.

Even a 1–2 mm distortion in a battery box or machine cover can cause assembly or safety issues. - Sublimation and decomposition – some high temperature materials, such as graphite or certain ultra-high-temperature ceramics, do not melt in a conventional way.

They transition directly from solid to gas or change chemical phase before melting.

For procurement teams comparing high temperature metals or refractory metals, focusing only on the highest melting point alloy can therefore be misleading.

The real concern is the temperature window where the part remains both mechanically reliable and dimensionally accurate.

Why Standard Melting-Point Values Are Only a Starting Point

Metal melting point charts and handbooks list values measured on pure samples under stable laboratory conditions.

These values are useful benchmarks, but fabricated components behave differently.

In actual production:

- Welding introduces localized heat far above the average part temperature.

- Bending and forming add residual stress into the metal.

- Machining, punching, and cutting alter the microstructure near edges and surfaces.

- Coatings and platings often have much lower heat resistance than the base metal.

- Repeated heat cycles cause fatigue, creep, or phase changes over time.

A buyer who understands these gaps between lab data and factory reality can ask better questions in RFQs, interpret technical offers more accurately, and select more reliable suppliers for high-temperature metal components.

What Determines a Material’s Melting Point — A Procurement-Relevant View

A material’s melting point originates from atomic bonding and crystal structure.

You do not need to be a physicist; you just need to know the main trends and how they influence industrial metal materials.

Bond Types and Lattice Density

Metals, ceramics, and carbides are held together by different types of bonds:

- Metallic bonds share electrons across a lattice.

Dense, stable metallic lattices typically result in higher melting points, which is why tungsten leads the list of high temperature metals. - Ionic and covalent bonds, common in ceramics and carbides, are even stronger.

They create some of the highest melting point materials known, but often at the cost of brittleness and poor toughness.

This explains why pure tungsten sits at the top among metals, while compounds such as hafnium carbide (HfC) and tantalum carbide (TaC) sit even higher on the melting scale as ultra-high-temperature materials.

Alloy Composition, Impurities, and Electron Behavior

Real industrial materials are almost always alloys, not pure elements.

Small additions of chromium, nickel, molybdenum, carbon or other elements can raise or lower melting behavior and change how strength drops with temperature.

Impurities or non-metallic inclusions can become weak points under heat, reducing the effective thermal resistance.

Even within the same nominal grade, batches from different mills can behave differently if process control is inconsistent.

For overseas buyers, this is one reason to pay attention to certificates, grade notation, and supplier quality systems.

A manufacturer like YISHANG that uses stable, traceable material sources and proper incoming inspection will deliver more predictable high-temperature behavior than a low-cost shop using mixed or unverified stock.

The Highest-Melting Materials — Metals, Alloys, and Compounds

When people ask what substance has the highest melting point, they are usually interested in an absolute record holder.

In reality, several classes of materials dominate different categories.

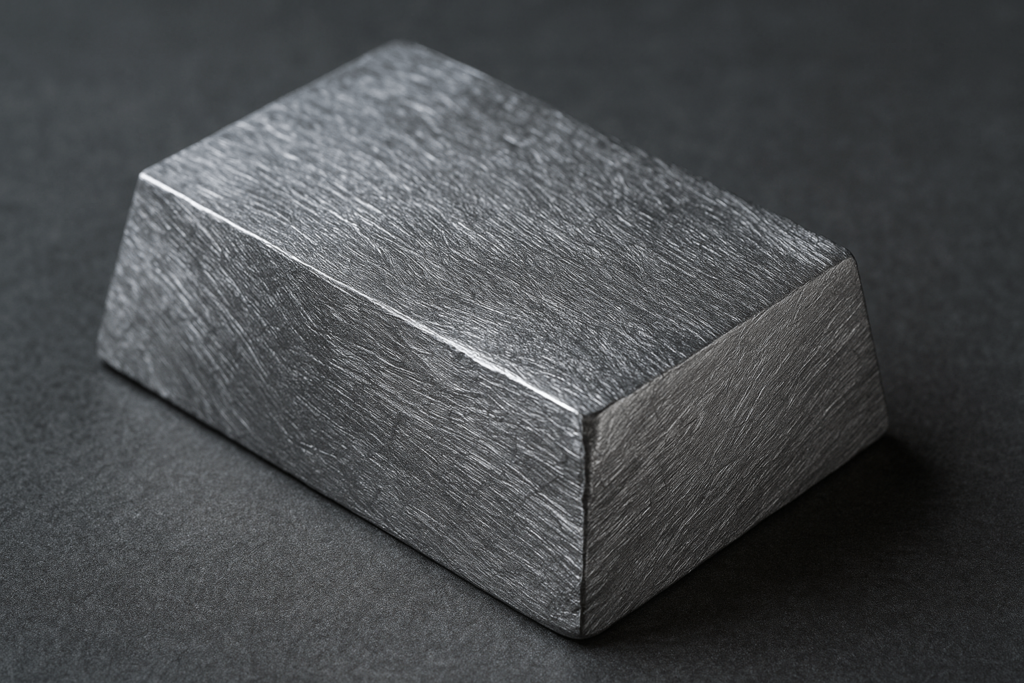

Tungsten — The Highest-Melting Metal

Among metallic elements, tungsten (W) has the highest melting point, around 3422 °C.

It is the benchmark for high temperature metals and is widely used for furnace components, lamp filaments, and critical aerospace hardware.

From a procurement perspective, however, tungsten has significant constraints:

- It is very hard and brittle at room temperature, which makes conventional forming and machining difficult.

- It often requires specialized joining processes (brazing, diffusion bonding, or advanced welding techniques).

- It is considerably more expensive than steels, stainless steels, or aluminum alloys.

Tungsten belongs to a small group of applications where extreme heat resistance is non-negotiable.

It is rarely a realistic candidate for standard sheet-metal products, cabinets, racks, or general industrial enclosures.

Highest Melting Point Alloy — Tungsten–Hafnium Carbide (WHC)

For the specific query highest melting point alloy, industry and research sources often point to tungsten–hafnium carbide (WHC).

This system combines the high melting behavior of tungsten with carbide phases to achieve one of the highest melting temperatures reported for an alloyed material.

WHC and related refractory alloys are used in:

- aerospace thermal protection systems,

- high-performance nozzles and inserts,

- industrial tools exposed to extreme heat,

- defense and scientific hardware.

For most buyers, WHC is more of a reference point than a practical choice.

Its cost, processing difficulty, and niche supply chain make it unsuitable for typical fabrication projects, but understanding that such an alloy exists helps frame where standard industrial alloys sit on the thermal spectrum.

Ultra-High-Temperature Ceramics (UHTCs) — Ta₄HfC₅ and Similar Compounds

Beyond metals and alloys, certain carbides and carbonitrides form a family of ultra-high-temperature ceramics.

Compounds like tantalum hafnium carbide (Ta₄HfC₅) are frequently cited in academic literature as candidates for the highest melting temperature material known, with reported melting points above 4000 °C.

These UHTCs offer extraordinary heat resistance, but:

- they are brittle and sensitive to shock,

- they are challenging to shape into complex parts,

- their production routes are expensive and specialized.

They are mostly used in hypersonic vehicle leading edges, rocket components, and experimental setups—far beyond the typical scope of commercial metal fabrication.

Carbon Allotropes — Graphite and Diamond

Carbon behaves differently from typical metals and ceramics.

Graphite, for example, does not melt at atmospheric pressure; it sublimates at very high temperatures, which makes it useful in furnace linings, crucibles, and molds.

Diamond converts to graphite before melting under normal pressure.

These carbon materials demonstrate why highest melting temperature alone cannot define performance.

Oxidation resistance, mechanical behavior under load, and environment (vacuum, inert gas, air) all play major roles in real-world suitability.

Why “What Has the Highest Melting Point?” Is Not Enough for Sourcing Decisions

By now, the pattern is clear: the materials at the very top of a melting point ranking are not the ones you will usually specify for metal cabinets, racks, machine covers, or structural frames.

Measurement Challenges at Extreme Temperatures

Above about 3500 °C, measuring melting points becomes extremely difficult.

Containers melt, samples evaporate, and instruments struggle to deliver consistent results.

Different research groups may report different values for the same compound depending on methodology.

For industrial buyers, arguing about whether one carbide melts 50 °C higher than another does not change sourcing decisions.

What matters is how commercial alloys behave in the realistic operating range of your equipment—often between 80 °C and 800 °C.

Lab Values vs Fabrication Reality

Most fabricated metal parts never reach their official melting point, but they still face heat-related risks during processing and service:

- distortion during welding, brazing, or heat treatment,

- loss of strength or stiffness at elevated temperature,

- cracking due to thermal shock or fatigue,

- coating failure and accelerated corrosion.

A high melting point alloy can still perform poorly if it is thin, poorly supported, or processed with excessive local heat.

This is why experienced buyers pay attention to softening behavior, yield strength at temperature, and recommended service temperatures, not just melting points.

Manufacturability, Lead Time, and Cost

Even if a material looks perfect on a thermal chart, it may not be appropriate for production.

If it is hard to cut, bend, weld, or finish, you can expect higher cost, longer lead times, and more process risk.

Procurement teams typically look for stable, commonly available industrial alloys that provide adequate heat resistance, good manufacturability, and predictable lead times.

Very few projects genuinely require the absolute highest melting point alloy or the highest melting point material on Earth.

How Melting Point Influences Purchasing Decisions and Supplier Evaluation

Used correctly, melting-point knowledge helps buyers choose better materials and evaluate suppliers more objectively.

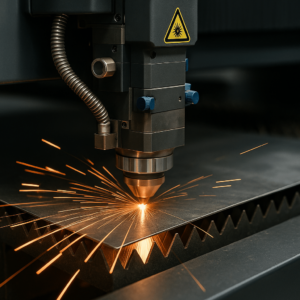

Weldability and Process Control

If your design uses aluminum, brass, or thin gauge stainless steel, welding must be carefully controlled.

These materials have lower effective heat tolerance, and the risk of distortion or burn-through is higher.

For higher temperature steels and stainless steels, weld heat-affected zones still require attention to avoid loss of toughness.

When comparing suppliers, it makes sense to ask:

- how they control welding heat-input,

- what experience they have with your specified alloy,

- how they fixture and clamp parts to minimize distortion.

A manufacturer that can discuss melting point, softening, cooling rates, and distortion in practical terms is usually a safer choice for heat-sensitive metal work.

Dimensional Stability and Mechanical Strength at Temperature

Even metals with relatively high melting points can lose a large percentage of their strength at half that temperature.

Frames carrying load in hot environments, cabinets near engines, or housings in ovens must retain stiffness and shape across the full duty cycle.

For example:

- Aluminum alloys melt around 660 °C but begin to lose significant strength well below 250–300 °C.

- Carbon steel melts above 1400 °C, yet its mechanical properties drop quickly beyond 500–600 °C.

Understanding this gap helps buyers judge whether a given design will remain safe and reliable under realistic operating conditions, rather than just trusting theoretical melting values.

Coatings, Finishes, and Thermal Compatibility

Many industrial parts use zinc coating, powder coating, or specialized paint for corrosion resistance and appearance.

These layers often degrade at temperatures where the metal substrate is still structurally sound.

If your product will be exposed to continuous heat, radiant heat, or occasional overheating, it is worth confirming:

- the maximum service temperature of the coating or finish,

- how repeated heat cycles affect color, gloss, and adhesion,

- whether high-temperature paint, ceramic coatings, or bare stainless steel might be more appropriate.

A technically mature supplier will proactively raise these issues during DFM (design for manufacturing) discussion instead of simply “building to print”.

Application-Driven Material Selection

Different sectors push metals into different thermal regimes:

- EV battery systems / energy storage – require stable, non-deforming enclosures and brackets around localized hot spots.

- Industrial ovens, dryers, and food equipment – need housings and internal structures that resist warping and coating failure.

- Agricultural and construction machinery – may see intermittent high heat plus shock loading, calling for robust steels rather than low-melting alloys.

- Vending, medical, and electronics enclosures – usually operate at moderate temperature but still benefit from understanding how coatings and stainless grades behave.

Using melting-point awareness as a filter, buyers can quickly rule out unsuitable materials and focus discussions with suppliers on the most appropriate alloys and thicknesses.

A Practical Melting-Point Reference for Common Fabrication Metals

To anchor this discussion, here is a simple reference for metals frequently used in industrial metal fabrication and custom metal parts.

| MaterialApprox. Melting RangePractical Notes for Buyers | ||

|---|---|---|

| Stainless Steel 304 / 316 | 1375–1530 °C | Good high-temperature resistance; ideal for many enclosures and frames |

| Carbon Steel | 1425–1540 °C | Strong and economical; strength falls above ~500–600 °C |

| Aluminum Alloys | ~660 °C | Lightweight; low melting and softening temperatures |

| Copper | 1084 °C | Excellent conductor; not ideal for structural high-heat areas |

| Brass | 900–940 °C | Easy to machine; limited structural strength at temperature |

This table does not replace detailed datasheets, but it gives procurement teams a quick reality check.

If your operating conditions approach the softening range of a chosen alloy, it is worth discussing alternative materials or design modifications with your supplier.

Conclusion — Using Melting-Point Knowledge to Reduce Risk and Improve Sourcing

Melting point is a powerful concept, but it is only one part of successful sourcing.

For overseas industrial buyers, the best results come from combining melting-point awareness with a clear understanding of weldability, dimensional stability, coating behavior, and the actual temperature range of your application.

The highest melting point material in theory will almost never be the best choice for a high-volume industrial project.

What really matters is choosing high temperature metals and alloys that can be fabricated efficiently, perform reliably in real conditions, and stay within your project budget and lead time targets.

A manufacturing partner like YISHANG applies these principles every day when producing metal products for international customers.

If you have drawings, target temperatures, or specific industry requirements, you are welcome to share them with us—we can help you evaluate suitable materials, from standard industrial alloys to higher heat-resistant options, and support you in making confident, low-risk procurement decisions.